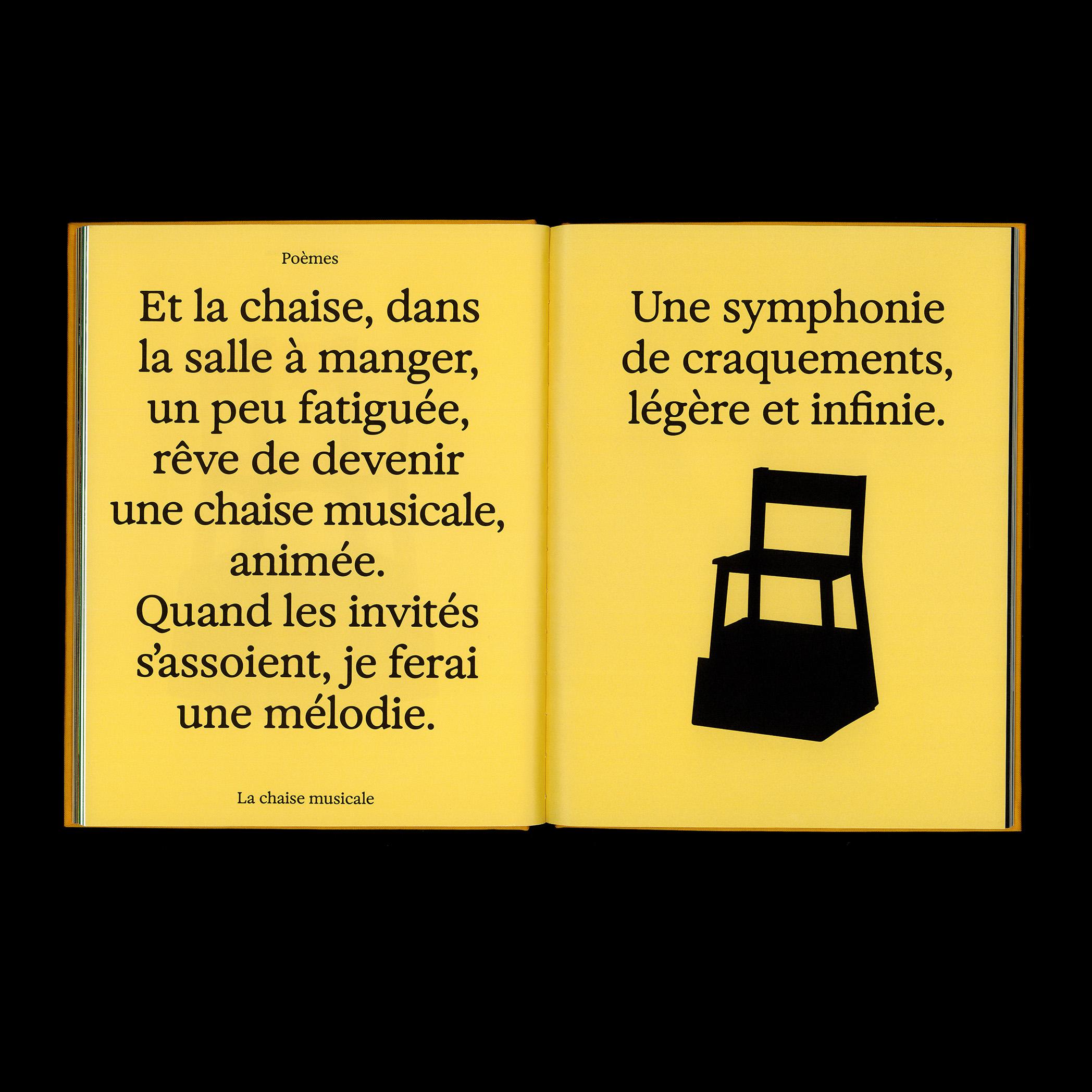

Exposure borrows the eponymous principle from photography, using it to question the possibilities offered by variable fonts in a completely original way. While studying at the Atelier national de recherche typographique (Nancy, France), Federico Parra Barrios took a very unique approach to the technique, developing a singular typeface between 2019 and 2022.

Available in Roman and Italic, Exposure is a remarkable feat—both technically and in terms of drawing—that shows how other ways of exploiting variable font technology are possible.

While variable fonts—which appeared in 2016—are considered to be a major development in typography, the use of axes of variation to modify weight, set-width, and optical size are all transformations inherited from previous techniques. Federico Parra Barrios breaks away from this conventional approach to propose a new way of thinking.

Exposure’s axis of variation ranges from –100 to +100, and gives a feeling of adjusting the intensity of the light to which the typeface is exposed, thus affecting its outline. Some might see this as a nod to another, now defunct, technique: phototypesetting.

At zero, the typeface is sharp and crisp. As the index decreases, the font becomes increasingly underexposed. The typeface seems to deform and becomes overwhelmingly black. The counterforms are filled almost to the point of illegibility.

Conversely, as the index increases, so does the light intensity. The original line is somehow overexposed until parts of it vanish as if burned by the light.

Federico Parra Barrios has carefully sculpted many intermediate designs in-between these extremes. In its static version, Exposure is also available in 21 different intensities of light. With the variable version, the user is free to select the index according to their needs and, of course, dynamically exploit the technology to create animations.

42 Styles

Roman

Italic

2 Variables

Roman

Italic

OpenType Features

Character Map

2

Supported Languages

▼

- Abenaki

- Afaan Oromo

- Afar

- Afrikaans

- Albanian

- Alsatian

- Amis

- Anuta

- Aragonese

- Aranese

- Aromanian

- Arrernte

- Arvanitic

- Asturian

- Atayal

- Aymara

- Azerbaijani

- Bashkir

- Basque

- Belarusian

- Bemba

- Bikol

- Bislama

- Bosnian

- Breton

- Bulgarian

- Romanization

- Cape Verdean

- Catalan

- Cebuano

- Chamorro

- Chavacano

- Chichewa

- Chickasaw

- Chinese Pinyin

- Cimbrian

- Cofan

- Cornish

- Corsican

- Creek

- Crimean Tatar

- Croatian

- Czech

- Danish

- Dawan

- Delaware

- Dholuo

- Drehu

- Dutch

- English

- Esperanto

- Estonian

- Faroese

- Fijian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Folkspraak

- French

- Frisian

- Friulian

- Gagauz

- Galician

- Ganda

- Genoese

- German

- Gikuyu

- Gooniyandi

- Greenlandic

- Greenlandic Old

- Orthography

- Guadeloupean

- Gwichin

- Haitian Creole

- Han

- Hawaiian

- Hiligaynon

- Hopi

- Hotcak

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Ido

- Igbo

- Ilocano

- Indonesian

- Interglossa

- Interlingua

- Irish

- Istroromanian

- Italian

- Jamaican

- Javanese

- Jerriais

- Kaingang

- Kala Lagaw Ya

- Kapampangan

- Kaqchikel

- Karakalpak

- Karelian

- Kashubian

- Kikongo

- Kinyarwanda

- Kiribati

- Kirundi

- Klingon

- Kurdish

- Ladin

- Latin

- Latino Sine

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Lojban

- Lombard

- Low Saxon

- Luxembourgish

- Maasai

- Makhuwa

- Malay

- Maltese

- Manx

- Maori

- Marquesan

- Meglenoromanian

- Meriam Mir

- Mirandese

- Mohawk

- Moldovan

- Montagnais

- Montenegrin

- Murrinhpatha

- Nagamese Creole

- Nahuatl

- Ndebele

- Neapolitan

- Ngiyambaa

- Niuean

- Noongar

- Norwegian

- Novial

- Occidental

- Occitan

- Old Icelandic

- Old Norse

- Oshiwambo

- Ossetian

- Palauan

- Papiamento

- Piedmontese

- Polish

- Portuguese

- Potawatomi

- Qeqchi

- Quechua

- Rarotongan

- Romanian

- Romansh

- Rotokas

- Sami Inari

- Sami Lule

- Sami Northern

- Sami Skolt

- Sami Southern

- Samoan

- Sango

- Saramaccan

- Sardinian

- Scottish Gaelic

- Serbian

- Seri

- Seychellois

- Shawnee

- Shona

- Sicilian

- Silesian

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Slovio

- Somali

- Sorbian Lower

- Sorbian Upper

- Sotho Northern

- Sotho Southern

- Spanish

- Sranan

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Swazi

- Swedish

- Tagalog

- Tahitian

- Tetum

- Tok Pisin

- Tokelauan

- Tongan

- Tshiluba

- Tsonga

- Tswana

- Tumbuka

- Turkish

- Turkmen

- Tuvaluan

- Tzotzil

- Ukrainian

- Uzbek

- Venetian

- Vepsian

- Volapuk

- Voro

- Wallisian

- Walloon

- Waraywaray

- Warlpiri

- Wayuu

- Welsh

- Wikmungkan

- Wiradjuri

- Wolof

- Xavante

- Xhosa

- Yapese

- Yindjibarndi

- Zapotec

- Zarma

- Zazaki

- Zulu

- Zuni